**Note: this report was written as my final project for Film History/Historiography with Dan Streible at New York University, hence why its different from my other content thus far. It may be getting posted to another blog site as well; stay tuned!

In addition to cult classics and commercial releases, the National Film Registry list is peppered with a number of home movies. One such standout on the list is the home movies of Cab Calloway, the jazz singer, songwriter, and bandleader who performed frequently in Harlem’s Cotton Club and had a career that endured for more than 65 years. After reviewing the home movies and learning more about Calloway’s trailblazing life, one gets a sense of their uniqueness and necessity on a list like this.

Who was Cab Calloway?

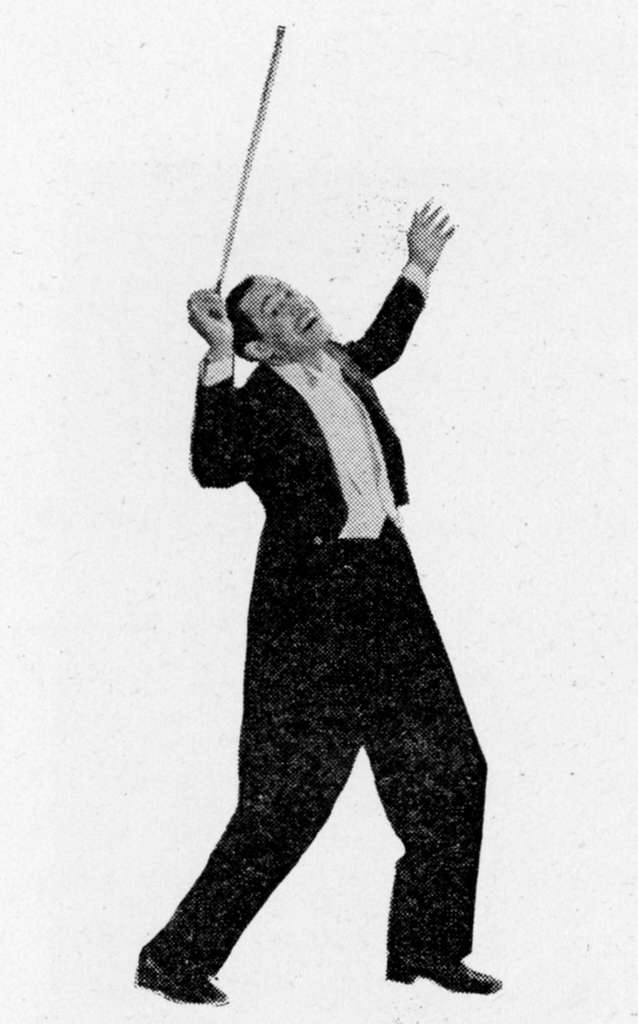

Cab Calloway. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons.

Cabell Calloway III was born on December 25, 1907 in Rochester, New York. In his autobiography Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, Calloway notes that “people have always tried to make something out of the fact that I was born on Christmas,”1 a throughline in how he spoke about himself as a “celebrity in terms of the public, but inside of myself…still a guy who used to hustle newspapers in the streets of Baltimore and stood in awe of talented musicians.”2 As a child, he was rambunctious but multitalented, excelling in sports (especially basketball) and as a vaudeville performer. He described this mixing of qualities and how it manifested from a young age:

“I was a combination of that old wildness that had gotten me into so much trouble and of the industrious, hustling moneymaker who helped to support the family. I’ve been a combination of those two qualities ever since. I’ve always worked hard and hustled to make money to take care of the people I love; and I’ve always been somewhat wild and independent.”3

As a child, Calloway was in segregated Baltimore schools, and as such, did not really experience integration—and attempts at integration—until he was an adult. One fact of note is that his oldest daughter Camay Calloway Murphy was

“one of the first Black principals in Baltimore’s public schools, Murphy broke down racial barriers and set new standards for arts-focused education. She championed the inclusion of music and cultural history in classrooms, recognizing the arts as a tool for self-expression and cultural pride. Her programs and initiatives introduced countless students to jazz, opening doors for them to explore their heritage and find inspiration through music.”4

Camay Calloway Murphy. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

As a light-skinned Black man, Calloway remembered times in his life where he was rejected by other African American people or accused of playing into stereotypes or not deviating his performances enough from minstrelsy. For example, an anonymous letter to the editor criticized Calloway’s performance of Kickin’ the Gong Around in the movie The Big Broadcast of 1932, because “kicking the gong” refers to opium and Calloway mimed snorting cocaine and shooting heroin in the performance. They wrote: “It was a shame and a blot on the Negro race. How can we train our children to aim higher in life after seeing and listening to the Calloway rhythm?” Booker T. Washington High School student Elfreda Sandifer countered:

“To a certain extent, I do think Cab Calloway clowns, yet the type of clowning that he does is new and original. Cab has been copied by white orchestras as well as Negro bands. Yet he has been able to produce his own work much better than any one [sic] else.”5

The Cotton Club and The Singing Kid (1936)

Cab Calloway worked his way up in big bands at first, eventually cementing Cab Calloway and His Cotton Club Orchestra as a mainstay at the Harlem location; they filled in for Duke Ellington and his band when they were unavailable. He remembered the Harlem Renaissance period, and how it made whole neighborhood “a center of Negro culture”:

“At that time the Cotton Club was the place to be, and I was absolutely awed by it all—the people, the glitter, the fast life, the famous celebrities. The best singers, comedians, dancers, and musicians all seemed to have come together to one place at one time. We played in the Cotton Club whenever Duke had a gig somewhere else, but the first time we were in there for any length of time was the summer of 1930, when Duke took his band to Hollywood, where he became the first Negro to have an orchestra in a major film.”6

Calloway conducting his band. Credit: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Though a landmark achievement, the Cotton Club was “a venue situated in the heart of Harlem that featured black star performers but allowed only white patrons through its doors”; accounts say that Black people could get in...if they could pay the exorbitant entry fee. Some critics have pointed out that the Cotton Club played into the minstrel image and diluted Harlem culture to be palatable enough for clientele, while others have noted that Calloway and his orchestra treated the club as “an experimental laboratory in which new musical techniques, devices, and procedures were explored.”7

Calloway co-wrote Minnie the Moocher with Irving Mills, which became his first big hit and the “theme song” for the Cotton Club Orchestra; the song was added to the Library of Congress National Recording Registry in 2018. In a guest post commemorating the song’s induction, Herb Boyd noted that

“Calloway, with his dynamic stage presence, perfect diction, and linguistic versatility, took the [scat singing and call-and-response] style to another level of popularity…his composition, ‘Minnie the Moocher,’ with its sexual innuendoes, references to cocaine and other drugs, and being about a bawdy woman of the night, was like an anthem to low-life communities. And Harlem was probably the location he had in mind.”8

However, the song drew some ire from critics, who accused Calloway of playing into stereotypes and using words and phrases generally unknown to any white visitors to the Cotton Club or any white listeners to a radio broadcast. Sloan reminds us that “hearing Calloway’s slang as culturally bankrupt...obscures the inherent play and theatricality embedded in the Harlemaestro’s performance,” arguing that “Calloway’s use of jive as a performance of hip Harlem, rather than as authentic representation, re-situates his vocabulary as a mix of reportage from city streets and creative invention.”9

Calloway and his band in a sleeper car. Credit: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

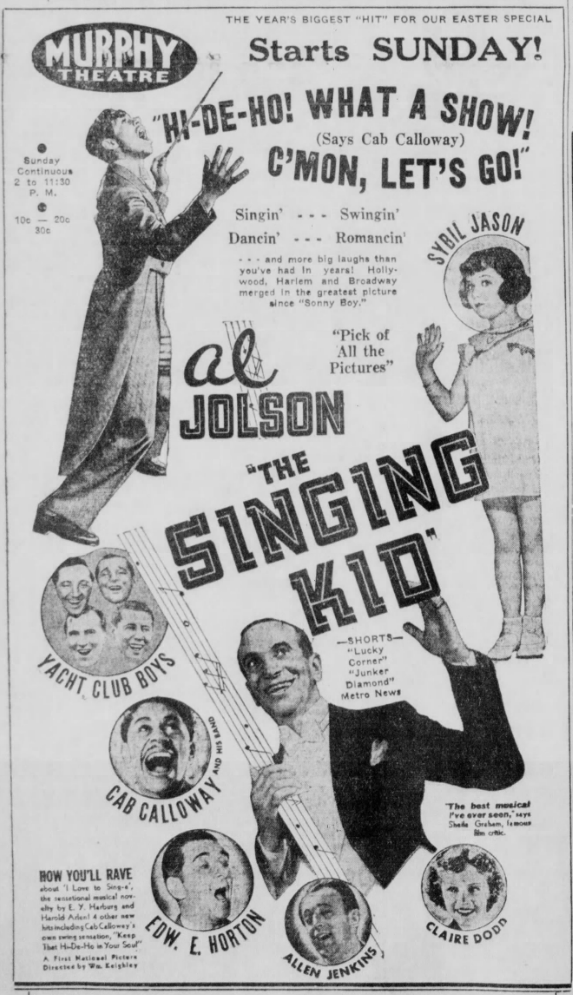

Calloway also made two movie appearances as himself in The Big Broadcast of 1932 (1932) and International House (1933). Wanting to achieve in the same way Ellington had, Calloway “went into [Cotton Club manager Frenchy] DeMange’s office and told him that [he had] heard Al Jolson was doing a new film on the Coast, and since Duke Ellington and his band had done a film, wasn’t it possible for [him] and the band to do this one with Jolson.”10 Just like that, the group reached a new level of critical renown when they were cast in The Singing Kid (1936). Not even a decade before, Jolson had been a part of cinema history, when Jazz Singer (1927) was the first motion picture with synchronized sound and music. Unfortunately, The Singing Kid sees the return of Jolson’s blackface as well, prominently on display in several of the song and dance scenes and throughout promotional materials for the movie. Jean-François Pitet, who has written books on Calloway and runs the Hi-De-Ho blog, notes that Calloway and his band were asked to take publicity photos in whiteface to complement Jolson’s blackface, but refused.11 Vaughan A. Booker further notes that Calloway’s stance against this stunt caused “the black press [to take] note of Calloway’s opposition in this instance” and “[to indicate] their support for him as a commendable African American entertainer. They counted his refusal to perpetuate certain racial caricatures as a professional achievement.”12

Promotional flyer for The Singing Kid. Credit: The Hi-de-Ho Blog.

Another snag was Calloway’s music, and attempts to completely change his style in the movie.

“I had some pretty rough arguments with Harold Arlen, who had written the music. Arlen was the songwriter for many of the finest Cotton Club revues, but had done some interpretations for The Singing Kid that I just couldn’t go along with. He was trying to change my style and I was fighting it. Finally [Al] Jolson stepped in and said to Arlen, ‘Look, Cab knows what he wants to do; let him do it his way.’ After that, Arlen left me alone.”13

Despite these shortcomings, Calloway looked upon his time shooting for the movie as a great experience, even one where he felt that he was seen as an equal to his white counterpart. He elaborated:

“And talk about integration: Hell, when the band and I got out to Hollywood, we were treated like pure royalty. Here were Jolson and I living in adjacent penthouses in a very plush hotel. We were costars in the film so we received equal treatment, no question about it…We really lived in style; it was a hell of an experience.”14

Cab Calloway singing while holding a piece of sheet music. Courtesy: Pickpik.

The movie unintentionally “represented Calloway’s professional rise and the waning of Jolson’s career,” and despite the press’s praise—no doubt spearheaded by Warner Brothers—that this is “one of the best shows Al Jolson has ever done” (Film Daily) and a testament that “Al Jolson works hard [and] finishes stronger than he has done in his past two pictures” (Variety Daily), it is remembered for its shortcomings

“While this film was a commercial failure, it was also interesting—and ultimately incoherent—for its attempts to provide ‘an explicit autocritique of the old-fashioned content of Jolson’s past while maintaining some of his modernist form and style’ and also seeking ‘to both erase and celebrate boundaries and difference, including most emphatically the color line.’”15

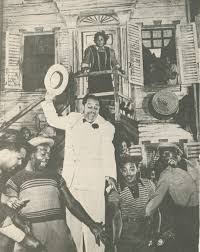

Another notable movie appearance was in Stormy Weather (1943), one of the first Hollywood films to feature a predominantly Black cast. Calloway and his orchestra’s performance of Jumpin’ Jive as The Nicholas Brothers perform the most incredible dance routine I’ve ever seen is a must-see in particular.

A lobby card for Stormy Weather, featuring stars Bill Robinson, Lena Horne, and Cab Calloway. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Shifts

Nuffie and Cab Calloway with two children. Courtesy: The Horse Head Blog.

After the movie, Calloway continued touring with his Cotton Club Orchestra, and through the mid-1940s, achieved a huge degree of success and fame and was able to travel the world. In 1942, he met Zulme “Nuffie” MacNeal and knew she was the woman for him.

“A mutual friend, Mildred Hughes from Washington, gave me her number because I was headed for a gig there. When I got into town I called her, and that whole week I was seeing Nuffie in between shows…I liked her a lot right off…She was not the run-of-the-mill woman I met on the road. She was proud, and aloof as all get out, and very intellectual. She kept me at arm’s length, but she was also very warm and friendly…Nuffie wasn’t sure at first that she wanted anything to do with me. And that was something new for me.”16

Still married at the time, Calloway spent the next six years divorcing his first wife Betty, with whom he had been essentially separated from for several years. To add insult to injury, Calloway had to disband the Cotton Club Orchestra due to poor financial decisions on his part, including an inclination towards gambling; for context, $200,000 in 1946 is the equivalent of over $3.3 million today.17

“The big band era came to an end for me in 1947, and the years after that are not easy to talk about. I went through some very rough times. I went from a guy whose gross was $200,000 a year to someone who couldn’t get a booking. From 1947 until 1950 there were times when I wasn’t sure that I would make it.”18

Eventually, a silver lining appeared for Calloway in his personal and professional lives. His divorce from Betty was finalized and his marriage to Nuffie took place in 1949, and he was cast as Sportin’ Life in the 1952-1953 revival of Porgy and Bess, which toured before staying at the Ziegfeld Theatre on Broadway. Gershwin originally modeled the character of Sportin’ Life on Calloway, and has been described as having been able to capture the character’s multifaceted nature well.19

Cab Calloway as Sportin' Life in Porgy and Bess. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Later Years

A spread in the May 1956 issue of HUE Magazine featuring Calloway and his daughter Cecilia "Lael" Calloway. Calloway's daughters Chris and Lael both went on to have professional singing careers. Courtesy: The Hi de Ho Blog.

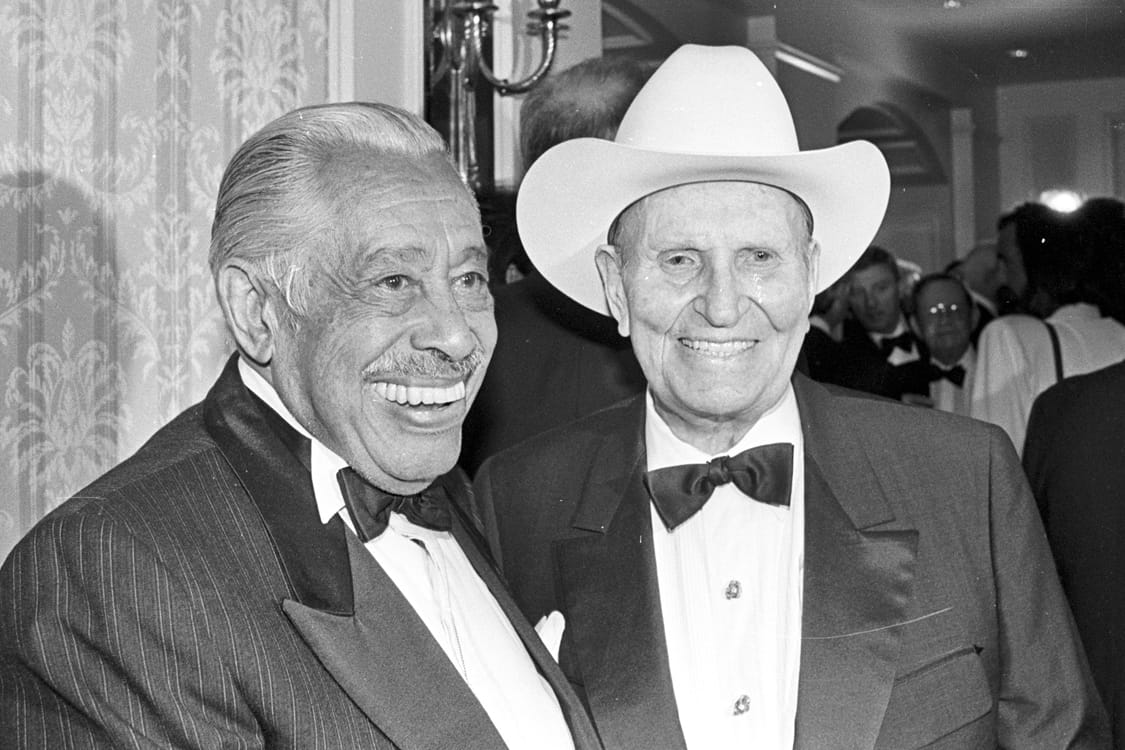

Over the next several decades, Calloway continued to record his own music, star in movies and stage productions, and began performing with his daughters Chris and Cecilia “Lael,” the latter of whom co-founded the Cab Calloway Foundation with their youngest sister Cabella. Famously, his last feature film appearance was as Curtis in The Blues Brothers (1980)—where he famously performs Minnie the Moocher—and one of his last recorded performances was in the music video for Alright by Janet Jackson. Calloway suffered a stroke in his home in June 1994 and passed away from pneumonia in November the same year at the age of 86, survived by his wife, five daughters, and seven grandsons.

Calloway and Gene Autry at the 1991 Songwriter's Hall of Fame ceremony, where Calloway received the Song Citation Recipient Award. Courtesy: The Official Cab Calloway website.

His Home Movies: The Why

Upon visiting the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) website and navigating to the Cabell “Cab” Calloway III collection, you can filter by object type and select “16mm (photographic film size),” then by object type “home movies” to see just those materials. There are six total, with five having the name “Cab Calloway Home Movie #1” through 5, then one called “Cab Calloway Home Movie: Haiti.”20 Half of these have been digitized and made available to the public via this website, but it is unclear what the status of the other home movies is. Even the ones without a video on their page have text descriptions of what occurs, so a visitor to the website can still get a sense of what occurs in all of the movies.

Calloway did not mention in his autobiography what started him on documenting travels and his family, or anything about recording memories in this way. He did, however, allude to parts of his personality that would have been surprising to fans and perhaps even acquaintances and friends.

“What am I like off the stage? I’m a loner, and sometimes even shy. That’s one of the reasons I think I can express certain personal things about myself better in a book than on the stage. And that’s why this book is important to me. I want people who have seen me and been my fans to get to know me better, to find out who the hi-de-ho man really is.”21

He explains later on what he means to categorize himself as being a loner:

“I have friends, bunches of friends, but I enjoy being alone and very few people know me well. Maybe there is nobody who really knows me well, inside and outside…Maybe the fact that I’m a loner explains why I love entertaining people. On the stage I’m all alone, but among people at the same time.”22

Additionally, he further elaborates how wonderful traveling in general was for him:

“Traveling to Europe has become so commonplace these days that it’s difficult for me to tell you how excited I was. A kid from Baltimore, with a little Chicago and New York slickness on the surface, and suddenly I was going to places that I had read about in school but never expected to see.”23

Why home movies at all? Especially for someone who was so introverted as he claimed in his private life and in the limelight for his entire adult life, why turn to documentation of another type? As Rick Prelinger notes in an essay appropriately titled “Home Movies,” “the home movie impulse is as old as cinema itself” and naturally, “early filmmakers often pointed cameras at friends and family.”24 He goes on to explain the trouble of archiving home movies, noting that community and regional archives “don’t collect to stockpile trophies but to document history, experience, and consciousness in a particular community.”25 And rather than question where home movies belong, Prelinger offers that “home movies belong with the families and communities that created them, but they also belong in a museum. Putting a home movie on a screen (whether large or small) rips it out of whatever we might imagine to be its original context, but it signals that the film is worthy of observation, perhaps even urgent to observe.”26

Capturing the quotidian or the unremarkable, as home movies are so want to do (the Calloway movies are no exception) is precisely their power. Prelinger explains

“We are likely to carefully study in a home movie what we are least likely to consider in our own lives. Just as watching someone try to tie a knot, unlock a stiff door, or start a stalled car awakens an irrepressible urge to jump in and do it ourselves, seeing home movies triggers self-reflection, empathy (or its opposite), or thoughtfulness. We observe others and rethink ourselves.”27

Calloway was not a perfect person and admits as much throughout his autobiography: he cheated on his first wife, had a temper that affected his relationship with his eldest daughter and soured some professional relationships, and he gambled and drank heavily at points in his life. It’s clear from his writings, interviews with his daughters, and the content of the home movies that especially as he aged, he made more of an effort to show the importance of family in his life. The shots of Trinidad and Tobago taken from a moving car may seem boring to some viewers, but you can see him as that child who never thought he’d travel the world, but who made it there after all. The actress and singer Lena Horne is featured in one of the home movies, not as a celebrity, but as a member of the extended family during a gathering. Even their milkman gets a special spotlight in one movie!

Contents

Home movies #1, 2, and 4 have been digitized and can be viewed on the NMAAHC page for each item. They are silent, which is immediately striking given Calloway’s career in music and sound.

Still from the first Calloway home movie. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The first home movie shows a family trip to Trinidad and Tobago, with several shots taken from a moving car. There are many panning shots over both students in a school and workers. There are many overexposed parts of the film and a lot of noise within the image, which give some images a haunting look. At just under 5 minutes, this video has the least amount of content and appears the most “touristy,” but remains an interesting look into this Caribbean spot at this point in history.

Nuffie with a baby. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The milkman after his milk delivery. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Actress Lena Horne interacting with the baby at a gathering. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Home movie #2 is various scenes at the Calloway home in Long Island and at the beach. There is severe overexposure along the edges of the film for its entire duration, which at times frames the subjects in an unintentional yet beautiful way. This one features a short clip of Nuffie holding a baby, who is prominently in this film. The next shot is of the milkman as he leaves a bottle of milk on the porch, looking pleasantly surprised and touched as he smiles and walks towards the camera then off screen. There are many shots of two of Calloway’s daughters as toddlers, along with other children and adults. This is the clip with Lena Horne, where she interacts with all the children but especially the baby, talking and pointing things out to her. The last three minutes of the movie include Nuffie and the baby at the beach, with the baby mostly taking in her surroundings and gently crawling along a blanket. There is a shot after the 10 minute mark of Cab carrying the baby, and Nuffie must have been shooting this footage.

Calloway and his band in the Teatro Solis in Montevideo, Uruguay. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Members of the band in front of a bus. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Nuffie in front of a bus. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Footage of a sunset. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Calloway walking a woman down the aisle for a backyard wedding. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The fourth home movie begins with the only color footage in the entire collection, showing part of a Calloway performance, which the metadata notes is taking place at the Teatro Solis in Montevideo, Uruguay. There are shots of crowds of people dancing and celebrating on the street and more scenery of Uruguay. The next roll shows various members of Calloway’s band outside of a hotel and their families, featuring several children who engage with the camera to various degrees. The group looks convivial, and you wish you could hear what they were saying, as they appear to be joking with Calloway as he’s shooting footage. The next scene shows Calloway escorting someone down the aisle of a backyard wedding; the metadata does not note who the woman is, though I would venture a guess that it’s one of Calloway's daughters. What follows is more scenes at the beach, this time with many more people. The final scene shows many people at what looks like an Argentinian asada, where people are eating grilled meat at long tables.

I recognize that describing the contents of videos is less fun than watching them yourself, and I encourage folks to watch these for full effect. While home movies #3 and #5 and the Haiti movie are not digitized, descriptions are available for their contents as well.

One throughline is that most of the film is likely shot by Calloway himself; he appears in some footage, in which case Nuffie is likely operating the camera. It is also good to contextualize when this film was being shot: in the wake of his divorce from Betty and marriage to Nuffie in 1949, at the tail end of an era of uncertainty in terms of his work in big band music, and just a few years before the 1954 Supreme Court landmark case Brown v. Board of Education. In his autobiography, he notes that “from 1947 on, whatever I’ve been through [my family has] been through. For good or bad.”28 Only one of the films shows Calloway as performer, and the viewer really gets to see the sense of wonder with which he was taking in these locales. The viewer also sees the care for family and friends in the home and beach scenes especially, where it is clear that Calloway is really trying to savor every moment with these people who are so dear to him.

One of the rare shots of Calloway within these home movies. Courtesy: The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

On its “How to Nominate Films” webpage, the Library of Congress notes that they

“strongly encourage the nomination of the full-range of American film-making: not just Hollywood classics or other well-known works, but also silent era titles, documentaries, avant-garde, educational and industrial films, as well as films representing the vibrant unmatched diversity of American culture, both in terms of content and all those who created these snapshots of America (sic) society: directors, writers, actors and actresses, cinematographers, and other crafts.”29

Given these credentials, I understand the inclusion of these home movies on the film registry. They represent a Black man who carved out a career for himself that spanned more than half a century, and who valued that his success could give his family a lovely life.

Conclusion

In the beginning of his autobiography, Calloway notes that while one of the purposes of writing the book is to entertain people, he also wants to tell his story. He says, “I’ve played a lot of roles, and now in this book I’d like to play the real one—Cab Calloway.”30 In the home movies, it feels as though he has done the same thing: showed us the real Cab Calloway. With federal funding and institutional uncertainty, it can feel scary to consider the future of this collection and others at NMAAHC and similar institutions, especially considering that not everything is digitized. However, I have hope that people will continue to turn to home movies like this as representations of their culture, personal windows into heritage, and glimpses of potential inspiration. That inherent need to document remains strong within us as individuals and members of many intersecting groups, and while that content may not look exactly the same as the Calloway home movies, I hope that people continue to see the importance of documenting their lives in this way and think about the best ways to share and preserve that material for years to come.

One of my favorite Shigeko Kubota pieces, called Meta-Marcel: Window. The wall text reads "video is window of yesterday./video is window of tomorrow." I think this piece sums up the appeal and power of home movies, while cleverly incorporating the medium of video. Courtesy: Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Cab Calloway and Bryant Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me (Cromwell, 1976), 8.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 143.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 32.

- Camay Calloway Murphy, jazz singer, educator and cultural advocate, dies at 94,” AFRO News, November 20, 2024, https://afro.com/camay-calloway-murphy-legacy/

- Nate Sloan, “Constructing Cab Calloway: Publicity, Race, and Performance in 1930s Harlem Jazz,” The Journal of Musicology 36, no. 3 (2019): 370, https://doi.org/10.1525/

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 105-106.

- Sloan, “Constructing Cab Calloway,” 371.

- Herb Boyd, “‘Minnie the Moocher’--Cab Calloway, 1931,” Library of Congress, 2018, https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/MinnieTheMoocher.pdf

- Sloan, “Constructing Cab Calloway,” 383-384.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 131.

- Jean-François Pitet, “The Singing Kid (1936),” The Hi-De-Ho Blog, January 15, 2006, https://www.thehidehoblog.com/blog/2006/01/the-singing-kid-1936

- Vaughan A. Booker, “‘Get Happy, All You Sinners,’” in Lift Every Voice and Swing: Black Musicians and Religious Culture in the Jazz Century, ed. Vaughan A. Booker (New York University Press, 2020), 67.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 131.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 131.

- Booker, “‘Get Happy, All You Sinners,’” 67.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 190-191.

- “Inflation Calculator,” US Inflation Calculator, https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 184-185.

- “George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess (Highlights),” Textura, April 2021, https://www.textura.org/archives/g/gershwin_porgy&bess.htm

- National Museum of African American History and Culture, “Cabell ‘Cab’ Calloway III Collection; Object Type: 16mm (photographic film size); Object Type: Home movies,” https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/collection/search?edan_q=*:*&edan_fq[]=set_name:"The+Cabell+“Cab”+Calloway+III+Collection"&edan_fq[]=object_type:"16mm+(photographic+film+size)"&edan_fq[]=object_type%3A"Home+movies"

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 4.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 32.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 135.

- Prelinger, Rick, “Home Movies,” in I Am Here: Home Movies and Everyday Masterpieces, Shedden, Jim, Alexa Greist, Rick Prelinger, and Robyn Lew, eds (Art Gallery of Ontario, 2022), 27.

- Prelinger, “Home Movies,” 32.

- Prelinger, “Home Movies,” 56.

- Prelinger, “Home Movies,” 29.

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 195.

- “How to Nominate Films,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/programs/national-film-preservation-board/film-registry/nominate/

- Calloway and Rollins, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, 4.

Works Cited

- Booker, Vaughan A. “‘Get Happy, All You Sinners.’” In Lift Every Voice and Swing: Black Musicians and Religious Culture in the Jazz Century, edited by Vaughan A. Booker. New York University Press, 2020.

- Boyd, Herb. “‘Minnie the Moocher’--Cab Calloway, 1931.” Library of Congress, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/MinnieTheMoocher.pdf

- Calloway, Cab and Bryant Rollins. Of Minnie the Moocher and Me. Crowell, 1976.

- “Camay Calloway Murphy, jazz singer, educator and cultural advocate, dies at 94.” AFRO News, November 20, 2024. https://afro.com/camay-calloway-murphy-legacy/

- “George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess (Highlights).” Textura, April 2021. https://www.textura.org/archives/g/gershwin_porgy&bess.htm

- “Inflation Calculator.” US Inflation Calculator. https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/

- Library of Congress. “How to Nominate Films.” https://www.loc.gov/programs/national-film-preservation-board/film-registry/nominate/

- National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Cabell ‘Cab’ Calloway III Collection; Object Type: 16mm (photographic film size); Object Type: Home movies.” https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/collection/search?edan_q=*:*&edan_fq[]=set_name:"The+Cabell+“Cab”+Calloway+III+Collection"&edan_fq[]=object_type:"16mm+(photographic+film+size)"&edan_fq[]=object_type%3A"Home+movies"

- Pitet, Jean-François.“The Singing Kid (1936).” The Hi-De-Ho Blog, January 15, 2006. https://www.thehidehoblog.com/blog/2006/01/the-singing-kid-1936

- Prelinger, Rick. “Home Movies.” In I Am Here: Home Movies and Everyday Masterpieces, edited by Shedden, Jim, Alexa Greist, Rick Prelinger, and Robyn Lew. Art Gallery of Ontario, 2022.

- Sloan, Nate. “Constructing Cab Calloway: Publicity, Race, and Performance in 1930s Harlem Jazz.” The Journal of Musicology 36, no. 3 (2019): 370-400, https://doi.org/10.1525/

Cab Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers performing "Jumpin' Jive" in Stormy Weather (1943).

An animation of Cab Calloway performing "St. James Infirmary" to a Betty Boop cartoon.

Cab Calloway performing "Minnie the Moocher" during the film Blues Brothers (1980), in his last feature film role.